contact me

Hi! I'm Lindsay Ferrier. You might remember me from a blog called Suburban Turmoil. Well, a lot has changed since I started that blog in 2005. My kids grew up, I got a divorce, and I finally left the suburbs for the heart of Nashville, where I feel like I truly belong. I have no idea what the future will hold and you know what? I'm okay with that. Thrilled, actually. It was time for something totally different.

The Surprising Story Behind Tennessee’s Trail of Tears

August 24, 2015

Did you know that you can walk on the actual Trail of Tears just 45 minutes away from Nashville?

It’s an incredible experience– especially if you know the back story. As it turns out, there’s a lot more to the Trail of Tears than we learned in our history books, and I think the information will surprise you. Read the story here, share it with your family, then visit the Trail of Tears for yourselves.

————————————————————————————

For me, this story begins with a house.

Specifically, this house:

Source: SGA.org

This is the historic Vann House. It’s located across the street from a gas station in Murray County, Georgia, where we often stop on our way to visit family. Once, while we were waiting for the gas tank to fill up, I looked the house up on my phone. What I found set my entire family down a path of discovery that changed the way we think about American History.

It turned out that this stately home was built by James Vann in 1804. What’s so special about James Vann, you ask? He was a Cherokee leader. That’s right. Not all Native Americans lived in wigwams or longhouses, as you’re about to find out.

You can tour the Vann House today and see its beautiful hand carvings, its innovative “floating” staircase, its 12-foot mantle, and many fine antiques. When James Vann died in 1804, his son Joseph inherited the mansion and became a Cherokee leader himself, eventually growing even wealthier than his father. But the Vanns’ fortunes changed forever in the 1830s, when the family was forced out of their home by the United States Army and told to go west to Oklahoma, by way of what would become known as the Trail of Tears.

This was Joseph Vann. Can you imagine this man and his family being kicked out of his family home by our government? As I read this story to Dennis and the kids and showed them the pictures, I had so many questions. This was not the Trail of Tears story I had learned about in school, nor was it the story told in my daughter’s American History textbook. It was pretty clear that this man couldn’t possibly have presented a threat to the white families around him — If anything, he was contributing to the US economy and reinforcing the notion that anyone with enough drive and ambition could ‘make it’ in the fledgling United States. How, then, could our government in good conscience force this family to leave?

Since my daughter was learning about this time in her history class, I did more research- Her textbook only devoted a page and a half to the Trail of Tears. It turned out that the Cherokee Indians of Northeast Georgia were very interested in adopting the ways of the white settlers- Realizing the white man wasn’t going anywhere any time soon, they took an ‘If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em’ approach.

By the 1790s, Cherokees had begun building plantations (some even owned slaves), growing crops like corn and cotton, keeping pigs, cattle and horses, and intermarrying with white families. They wore suits and dresses and practiced Christianity. They established schools to educate Cherokee children and some of the wealthier among them sent their children to private boarding schools in New England. Not all of the Cherokee agreed with this assimilation, but those who did (about 20,000 of them) banded together and created a capital city in North Georgia in 1825. They named it New Echota and there, they established their own government, modeled after our own, with executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

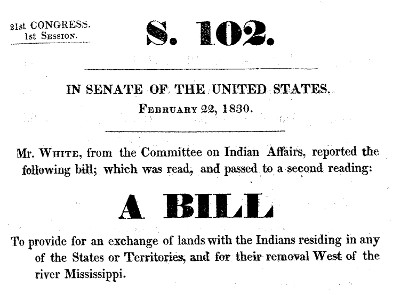

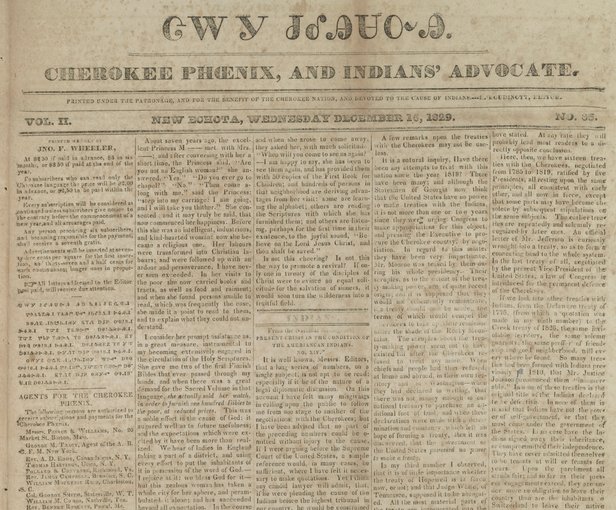

They wrote a constitution, elected a Principal Chief, and began publishing a newspaper written in their native language. Today, the state of Georgia owns what’s left of New Echota- It contains 12 original and reconstructed buildings, including the Council House, Court House, Print Shop, a missionary’s home, and an 1805 store.

Source: Native History Association

The events leading up to the Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears are well documented, so I won’t repeat them here. (The History Channel has a great Trail of Tears synopsis.) We’ll skip to 1838, when thousands of U.S. troops arrived at New Echota and began driving Cherokee Indians from their homes into prison stockades. One soldier who participated in the removal later wrote about it- He described soldiers arresting Cherokee men as they worked in the fields, dragging women from their homes, prodding the elderly and sick with bayonets to make them move faster, and often separating children from their families as they forced them to walk miles to the stockades. Once the Cherokee people were imprisoned, white looters ransacked their homes.

The Cherokee people lived throughout that summer in those stockades without adequate provisions for survival. Hundreds died there. They didn’t leave for their 1,000 mile journey to Oklahoma until October, when the air had grown chilly and a severe winter was on its way. “Many of these people didn’t have blankets,” the soldier wrote of their departure, “and many had been driven from home barefoot.” Before they began their journey, their Chief, John Ross, led his people in prayer.

Four thousand of the 16,000 Cherokee driven from their native land would end up dying before they reached Oklahoma.

It was this story that I told the kids, with the help of photos, video (linked below), and an excellent episode of This American Life.

And after that, there was only one thing left to do– Walk the Trail of Tears ourselves.

A certified portion of the actual Trail of Tears can be found at Port Royal State Historic Park in Adams, Tennessee, about 45 minutes from Nashville.

I had been wanting to visit this park for quite a while, but I’d read that there’s not much to it so I reserved spots for my family on one of its scheduled guided tours. Unfortunately, when we arrived for the tour, the park’s office was closed and not a soul was in sight. Apparently, the tour had been canceled and they had neglected to notify us.

Undaunted, we explored on our own- and I’m glad we did.

It’s hard to believe it now, but this small state park in the middle of nowhere was once a thriving port town known for its flatboat production. The foundation you see in the above photo used to be a tavern and inn for travelers.

Located at the head of the Red River, Port Royal was a shipping port for steamboats and flatboats and was also a stop on a major stagecoach line. Today, you can still see the remains of the foundations of stores, homes and warehouses here, the remains of the stagecoach road, and a Pratt Truss design steel bridge built in 1887.

Port Royal is also one of two documented stops in Tennessee for Cherokee Indians on the Trail of Tears. Here, soldiers escorting the Cherokee Indians set up camp and replenished supplies along their journey.

It was at Port Royal that Cherokee leader Elijah Hicks wrote a letter to Chief John Ross, telling him about the poor health of his people, who were “sorely in need of warm, winter clothing.” He also wrote that “a sense of despair at their exile has overtaken them. The people are very loath to go on.”

The Trail of Tears portion of the park is a 1/2-mile trail that includes 300 yards of the original path the Cherokee must have walked upon. We went on a summer day when the dense foliage provided welcome relief from the heat. But when the Cherokee people walked this trail, the trees would have been bare, the ground cold and hard.

After all we had learned, walking on the trail was a somber, moving experience.

We were the only ones on the trail that day and the woods were strangely silent, which seemed somehow appropriate. As we walked, I looked around for something, anything, that the Cherokee Indians would have seen while they were on this path- but 175 years later, it didn’t seem likely.

And then I saw this.

Beside the river, a massive oak with a trunk that would take at least a half-dozen people holding hands to encircle. Is this tree the sole surviving witness of the Cherokees’ Port Royal encampment? I think it might be.

The hike took about 30 minutes at an amble- a perfect amount of time to keep my 8 and 11-year-olds engaged and interested in the experience. In retrospect, I think I enjoyed the walk more than I would have with a guide- You can’t really take in the enormity of what you’re seeing unless you have a certain amount of silence to contemplate what happened. However, I’m told that if you call the park ahead of time, a ranger will take you around and tell you about the park’s points of interest. (Let’s just assume he or she will actually show up the next time around!)

Taking the time to research this story has taught my children so many important lessons. For one thing, it started the conversation about bias in history, and the fact that every eyewitness, every historian, every textbook author, is going to have opinions about what happen that inevitably seep into the narrative. We’ve decided that it’s important to get as many perspectives as possible when learning about a historic event, in order to get a more complete picture.

Source: National Park Service

This has also changed the way my children see the role of Native Americans in our nation’s history. Their textbooks include plenty of drawings and paintings of Native Americans in animal skins, hunting or sitting outside their wigwams. Legends and tales abound of Indians in the 1700s and 1800s who battled with white men over their land and murdered innocent pioneer families. But I certainly don’t recall ever seeing photos of Native Americans in my school history books who lived in houses and wore western clothing and owned plantations and published newspapers, and fought their battles through the nation’s court system. I don’t recall reading about these families being dragged from their homes without even being allowed to grab a pair of shoes, locked up in a pen for months, and then forced to walk a thousand miles to a land they had never seen.

My 11-year-old is also learning that the ‘heroes’ of children’s history books aren’t always honorable. In fact, I think my daughter’s exact words were, “I’m sorry, I know it’s wrong, but I hate Andrew Jackson.” Harsh words for a Tennessean, no? This prompted a conversation about how throughout history, pretty much all of our presidents have done some things right and some things very, very wrong, and we should never assume a historical figure was always perfect– or even in the right– just because a history book may make him or her seem that way. *cough* *cough* COLUMBUS *cough* *cough*

Source: Wikimedia Commons

We haven’t been to New Echota yet, but we plan to go soon- It’s only a few minutes away from where I grew up and I can’t believe I only recently learned of its existence. In the meantime, I hope you’ll consider taking your kids to Port Royal’s Trail of Tears and telling them about this little-known side of a story we all thought we knew.

If you’re going to Port Royal State Park, you might also want to make plans that day to tour Dunbar Cave, which is offering guided tours to the public again! Dunbar Cave includes Native American Mississippian hieroglyphs, dating from approximately 1350 AD. Th cave has been closed for a while, so I’ve never been, but I can’t wait to see it. Check the park’s website for upcoming cave tours.

Adams is also home to the legendary Bell Witch. Stop in town to see the log cabin of John Bell, or tour the Bell Witch cave where the spirit is said to live. In October, the town holds a really fun Bell Witch festival.

Want to teach this unknown Trail of Tears perspective to your kids? Here are some resources I used that I highly recommend.

-The official Vann House website includes a 15-minute, in depth video on the Vann House and the Vann family. It’s a little dry but it’s worth watching since it tells the story in detail and includes photos that make it all come alive.

-The New Echota website has another 17-minute video that also tells the story of this former capital of the Cherokee Nation. The narration could certainly use some work (i.e., 1950 called and wants its narrator back), but the photos and the story itself are really fascinating.

-The NPS partnered with the Cherokee Nation to create a video on the Trail of Tears. You can find links to it on the NPS website.

–Tennessee History for Kids is one of my favorite websites, and it has the best information on the history behind Port Royal that I’ve found online. Check it out!

-I just re-read Little House on the Prairie and loved it even more as an adult than I did as a kid. Laura Ingalls Wilder does a wonderful job of explaining through the story of her own life how white settlers felt about Native Americans, and why. I also appreciated that she didn’t lump them all into one category- The book includes stories of both good encounters with Native Americans and bad. The Wilder family was very nearly slaughtered by Indians, according to her account, but Indians saved their lives as well. In the end, I believe the Wilders’ kindness is what saved them, and this is a great perspective for children in particular. How could simple human kindness have changed the outcome of the Trail of Tears?

Keep up with all the turmoil by following me on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

In the 1970,s our family would vacation in the Smokey Mt. almost every year. We use to watch an outdoor play called Unto These Hills. It was a Play about the “Trail of Tears” Have you heard of this in your research??

I haven’t heard of it, Danny. It must’ve been good if you went to see it more than once! 🙂

I haven’t heard of it, Danny. It must’ve been good if you went to see it more than once! 🙂

Still going strong: http://visitcherokeenc.com/play/attractions/unto-these-hills-outdoor-drama/

Still going strong: http://visitcherokeenc.com/play/attractions/unto-these-hills-outdoor-drama/

Awesome!

Glad to know it is still going on it really made an impact on me as a kid as it does now. Thanks Linds for bringing up some good memories.

Glad to know it is still going on it really made an impact on me as a kid as it does now. Thanks Linds for bringing up some good memories.

Thanks K.D.

Thanks K.D.

Yes we would see it every time we went. It was in Cherokee NC. I will look thru some old pix and see if I have any. as a teenager it was awesome and saddning

Yes we would see it every time we went. It was in Cherokee NC. I will look thru some old pix and see if I have any. as a teenager it was awesome and saddning

In the 1970,s our family would vacation in the Smokey Mt. almost every year. We use to watch an outdoor play called Unto These Hills. It was a Play about the “Trail of Tears” Have you heard of this in your research??

Thanks for the great info, much of which was new to me. An official Trail of Tears marker is about a mile from our 1860s house located in Coopertown. It is easy to imagine the trail went thru the 600 acres of property that was owned by the original owner of our house. This house was a stage coach stop on the road between Springfield and Ashland City. The now very lightly traveled stage coach road still exists and I often sit on the front porch and try to conjure up what it must have been like to live here then.

What a wonderful place to live! You are very lucky. 🙂

Thanks for the great info, much of which was new to me. An official Trail of Tears marker is about a mile from our 1860s house located in Coopertown. It is easy to imagine the trail went thru the 600 acres of property that was owned by the original owner of our house. This house was a stage coach stop on the road between Springfield and Ashland City. The now very lightly traveled stage coach road still exists and I often sit on the front porch and try to conjure up what it must have been like to live here then.

I would love to do this when my kids are a little older. I’m part Cherokee myself, and I am also very passionate about history. There is something incredibly special to me about standing where history happened. There is a connection I feel that I can’t quite explain.

I would love to do this when my kids are a little older. I’m part Cherokee myself, and I am also very passionate about history. There is something incredibly special to me about standing where history happened. There is a connection I feel that I can’t quite explain.

[…] the actual Trail of Tears. Fall is a beautiful time to walk this historic trail, but before you go, read this little-known backstory about what happened there– It will make the experience much more meaningful to your family. You might even opt to wait […]

[…] https://somethingtotallydifferent.com/the-surprising-story-behind-tennessees-trail-of-tears/2015/08/24/ […]

[…] 21. Teach your children about one of the darkest days in Tennessee history by walking the Trail of Tears. Port Royal State Park isn’t far from Nashville and it includes a documented stretch of the actual Trail of Tears, where thousands of Cherokee Indians lost their lives on a forced march westward, away from their homes. Be sure and tell your children the backstory before you go- What we uncovered surprised us. You can read the full story about Tennessee’s Trail of Tears and what to expect at Port Royal … […]

[…] Teach your children about one of the darkest days in Tennessee history by walking the Trail of Tears. Port Royal State Park isn’t far from Nashville and it includes a documented stretch of the actual Trail of Tears, where thousands of Cherokee Indians lost their lives on a forced march westward, away from their homes. Be sure and tell your children the backstory before you go- What we uncovered surprised us. You can read the full story about Tennessee’s Trail of Tears and what to expect at Port Royal … […]

My grandfather was 100% Cherokee. It brings me to tears every time I try to go to a website that talks of the Trail of Tears. He use to go by the last name of Cornett. Which is a name on the Indian roll. Then for some reason or another his name was changed. His son said he would never speak of being an Indian or anything about them. Been trying to find out why he would have changed his name. Often wonder if it had something to do with The Trail of Tears….